In 2001, I read Fast Food Nation: The Dark Side of the All-American Meal. It explains not only what I put in my body at the drive-through window, but also what my money supports, everything from the way factory-farm animals are treated to the way the farms are managed. fast-food worker.

I haven’t tipped a nickel at a fast-food restaurant since. Not for a burger, not for a fry, not for a soda. Zippo, nada, bupkis.

In 2006, I read The Omnivore’s Dilemma: A Natural History of Four Foods. It explains where the food in my grocery store comes from, along with what my money supports, everything from the subsidized corn industry to the fossil-fuel industry.

I haven’t bought a single package of conventionally produced chicken, beef, or pork at the supermarket since. Not the wings, not the patties, not the chops. Diddly-squat, goose egg, zilch.

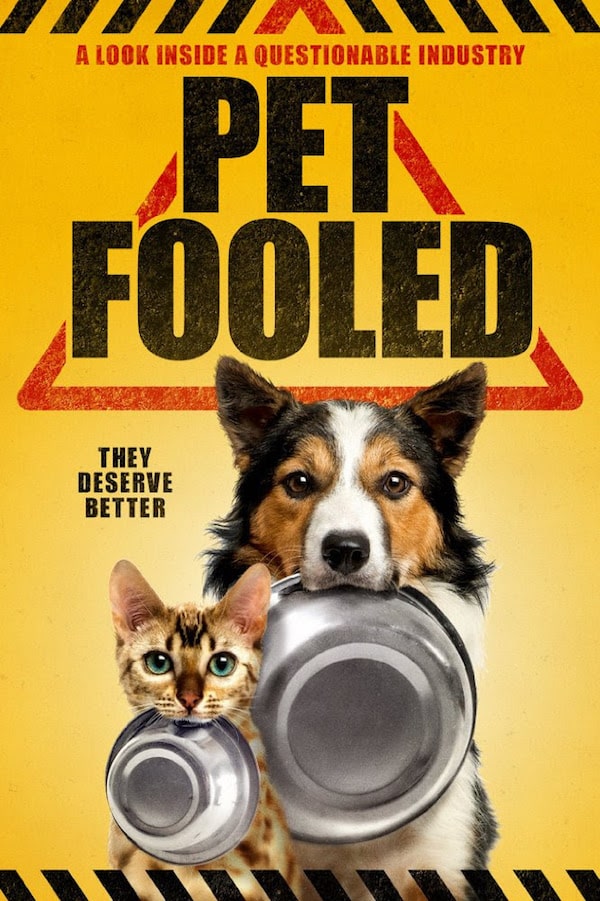

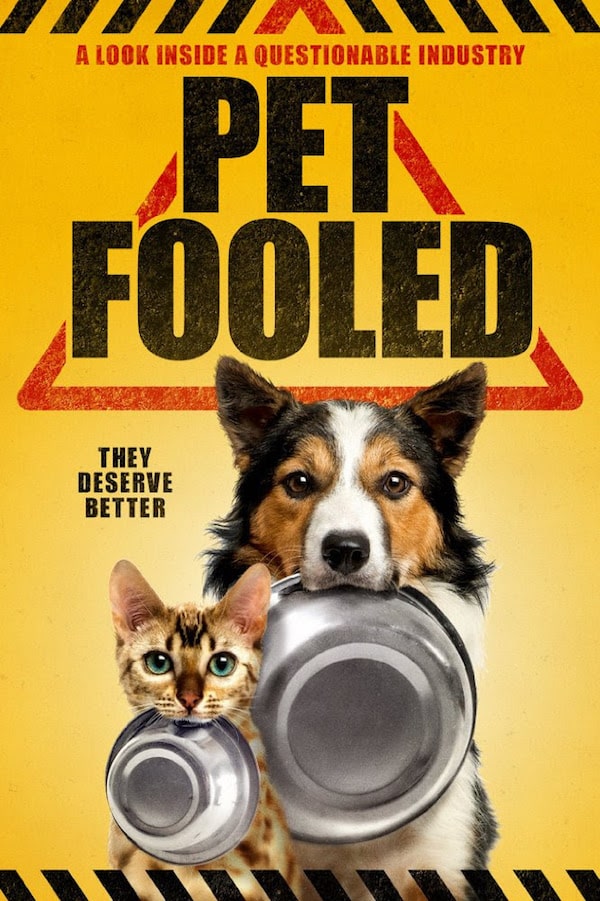

And now that I’ve seen the documentary PetfoolsI will never buy dog food the same way again.

The relationship we Americans have with food—even those of us trying to be conscious consumers—is evolving, and fast. Think back just 15 years: Few grocery stores had an organic section stocked with everything from Asian pears to cashew milk. There is no Whole Foods in all of Manhattan. And who has ever heard of kale or quinoa?

Today, the trend toward buying and eating healthier human foods has exploded, but in the field of pet food, this concept remains evolving. As with so many things involving our dogs, many of us never think about what we’re buying or why we’re buying it. Just as we used to never question what’s in our own food (or even more demanding of the companies that make it) many of us fail to ask: What is really in that dog food? Is it really good for my dog?

These are the questions in the new documentary Petfools challenge us to consider, in ways that should motivate us to change our shopping habits when it comes to our dog food, too.

One of the first scenes that caught my attention explained how the kibble became so plentiful. According to the movie, during World War II, a moratorium was placed on the use of cans as containers for dog food because the metal was needed for war. Pet food companies have to come up with other packaging, and wet food doesn’t work in paper or plastic bags.

Thus began the mass production of kibble, at the very time in American history when everyone moved to the suburbs, bought a house with a white picket fence and got a family dog. And just as few of our parents and grandparents asked about the kennel facts behind the cute puppies they bought from pet stores and breeders, or about what going on inside our shelters back then, hardly anyone asked what went into the kibble bags, either.

The truth, Petfools explanation, is that the change in packaging has given pet food manufacturers a way to change key ingredients without most dog owners noticing. Things like corn, wheat, and other less expensive, “biologically inappropriate” foods, the film says, are starting to show up—probably contributing to an increase in dog diseases ranging from diabetes to obesity in allergies.

And why would pet food companies change that financial-windfall formula, even though metal cans are now on the shelves? Most of us with dogs today have simply followed our parents’ lead, buying bags and cans of dog food without knowing what’s in it, and without a second thought.

Even if we try to read labels today, identifying the contents of dog food can be an exercise in frustration. Petfools Explains that if a bag or can label includes the words “dinner,” “formula,” or “nuggets,” then it must contain only 25 percent of the advertised meat or fish. If the label adds the word “contains”—such as, “contains chicken”—then the percentage of the ingredient required, Petfools said, down to just 3 percent. The word “taste” on dog-food packaging can mean zero trace of, say, the juicy steak pictured on the front of the bag, according to the film.

Most of us don’t bother to read labels anyway; only a few times in recent history have we thought there was reason to do so. There was a chicken jerky scare in 2011, with the discovery that certain treats from China were killing beloved pet dogs. Before that, in 2007, the big scandal was the death of dogs from kidney failure, leading to the recall of millions of packages of food.

Those incidents prompted some of us to start reading labels, but even with those massive recalls, the amount of pet food pulled off the shelves only accounted for 1 percent of all pet food in American stores, according to Petfools; episode was a blip, one that the $23 billion pet food industry easily overcame.

The filmmakers said they contacted all major pet food brands for comment, and that none would participate in the documentary. Of course, that’s why the pet food companies seem as trustworthy as the multinational companies that now control most of our human food supply, and have gone to the extreme of demanding an “ag-gag” law that makes it illegal for those of us who have questions about the origin of our food to take pictures inside an animal facility in some states.

If you think about it, the only thing that got the biggest human food producers to start changing their ways—even just a little—was consumers demanding better by giving our weekly food budget to those budding competitor. Our human food choices are finally improving now, some 15 years after I (along with millions of other people) realized what I was buying into by reading that first book and changing of my shopping habits.

Petfools all of us dog lovers are rightly encouraged to start using the same conscious-consumer approach to food that we buy food for our dogs, so that we can see more grain-free dog food, raw food dog, and other “biologically appropriate” options in pet supply stores in the coming years.

I’m on board. I read labels. And I don’t give another nickel to dog food brands that could be really bad for my pups. Zero, nothing, skadooch.